Someone (a professor of literature!) once looked me in the eye and, in all seriousness, told me that postmodernism didn't exist. I realized

then that he had missed far more than the point of the presentation I had just given—he had missed a major literary movement. Over the

years I've encountered a number of people who fervently adhere to their belief that there is no such thing as postmodernism. In literature, that

is. I've never heard anyone claim that there's no such thing as postmodernism in architecture. And so I had an idea. Why not use architectural

examples of modernism and postmodernism to help people understand the two movements in literature?

A Modern Building

Mies van der Rohe's Seagram Building, New York City

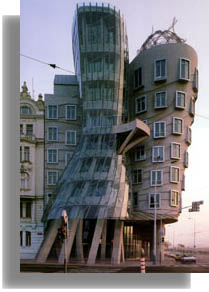

A Postmodern Building

Nationale-Nederlanden Building, Prague, Czech Republic

| Some general characteristics of the two movements that apply to both architecture and literature: | |

| Modernism | Postmodernism |

|

|

Download the entire chapter of my dissertation by clicking HERE. Or scroll down and read my "Criticisms and Conclusion" section.

Criticisms and Conclusion

Those who favor postmodernism criticize modernism for being elitist, pessimistic, nihilistic, didactic, and self-important. Those who favor modernism criticize postmodernism for being substandard, sporadic, cluttered, nihilist, American, and relativist. While these criticisms clearly reflect both generational differences and differences in taste, they can also provide additional insight into the two movements.

Modernism has been criticized for its elitism, sexism, racism, and general suppression of anything that is not white, heterosexual, bourgeois, and so forth. Of course changing societal views over the course of the last century have also changed the way people view these issues. At the same time, it is easy to see how countless pages devoted to capturing the stream of consciousness of a woman preparing for a party, as in the case of Clarissa in Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, 900 pages replete with the interior monologues of a group of men attending a six-hour provincial conference, as in the case of Kilpi's Alastalon salissa, or Marcel's extensive, meandering memories of his own life, as in Proust's A la Recherche du temps perdu [Remembrance of Things Past], can appear self-important.

Since modernism is criticized for its elitism, it makes sense that postmodernism is criticized for its populist leanings, its embrace of sub-literary genres, and its inclusion of popular cultural references. In particular, many traditionalists are threatened by postmodernists' penchant for leveling the playing field between high culture and popular culture. They equate this with a lowering of standards. In a recent newspaper debate in Norway, for example, Dag Solstad argued that allowing literature students to analyze jentelitteratur [popular fiction for young women] means that people believe these texts are just as good as texts by canonical greats such as Ibsen. A postmodernist is unlikely to feel threatened by the notion of comparing a work of adolescent fiction to Ibsen. Postmodernists do not assume the automatic hierarchical superiority of canonical authors such as Sigrid Undset, who received the Nobel Prize for literature, but instead feel that there is always the potential to gain insight by comparing works—for example, Undset's Jenny with Helen Fielding's Bridget Jones's Diary. Although Fielding will almost certainly never receive a Nobel Prize, postmodernists are likely to agree that the difference in academic acclaim the authors have received is not a reason to reject the idea of comparing the books outright. Whether the comparison proves apt or not, postmodernists agree that a respected work of literature cannot lose stature through a comparison. In other words, as Kjærstad writes in his response to Solstad, allowing students to write about jentelitteratur does not diminish Ibsen in any way. Kjærstad decries as utterly unreasonable Solstad's assertions that "akademikerne har mistet interessen for disputaser (når var Solstad på disputas sist?) eller at norsklærerne ikke verdsetter Ibsen høyere enn krimromaner (når snakket Solstad med en lærer)" [academics have lost interest in dissertation defences (when did Solstad last attend a defense?) or that Norwegian teachers don't appreciate Ibsen more than murder mysteries (when did Solstad last talk to a teacher?)] (Aftenposten 1 July 1997). Postmodernism's populism is partially a legacy of poststructuralism, which regards all knowledge as textual. If the definition of text is opened up in this way, it becomes possible to compare such seemingly divergent masterpieces as George Lucas's Star Wars movies and Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queen. In fact, in his delightfully postmodern Trash Culture, Simon shows that such a comparison can be extremely fruitful (29–37).

The modernist assumption that educated readers will understand French, German, Latin, or classical Greek and recognize allusions to literature in those languages is another reason some consider modernism elitist. Many modernists make the assumption that all educated people have read the same books and share the same educational backgrounds and values. Postmodernism's pluralist message, promoting inclusion of marginalized voices, was viewed as a threat and resulted in a wave of articles and books, such as E.D. Hirsch Jr.'s Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. There were similar outcries in Finnish and Norwegian newspapers from conservative academics and literary critics who bemoaned everything from falling standards, to children watching too much television, to no one attending dissertation defenses (cf. Solstad, Aftenposten 27 June 1997). Jon Hellesnes's satirical cautionary tale against the dangers of postmodernist thinking, Den postmoderne anstalten, is another example of a negative reaction. Methinks they do protest too much.

They have misunderstood postmodernism. As a movement, it does not seek to topple all that came before it. It merely asks readers to consider new pairings, to analyze literary greats in new contexts, to expand the definition of what makes great literature. Postmodernists criticize modernists for arbitrarily requiring all people to fit into an academic template that may not represent their backgrounds. Around the world, scholars and critics have also responded positively to postmodernism as a movement. Their responses have been less newsworthy, particularly in Scandinavia, than their aghast colleagues' dismay. After all, there is little in a calm, reasoned response to a literary movement that awakens popular notice. Numerous scholars in Norway and Finland have tackled the challenge of postmodernist literature—see for example Liisa Saariluoma's Postindividualistinen Romaani [The Postindividualist Novel], Bo Jansson's Postmodernism, Päivi Kosonen's Naissubjekti ja postmoderni [The Female Subject and Postmodernism], and Eivind Røssaak's Det Postmoderne og De Intellectuelle [The Postmodern and The Intellectual]. This ever-widening group of scholars reacted calmly and rationally to postmodernism as a movement and have not shied away from applying postmodernist theory to actual literature, something postmodernism's detractors seem unable to do. These scholars, who have taken postmodernism in stride, respond calmly to the changes postmodernism implies. For example, Lasse Koskela comments matter-of-factly on a Finnish Board of Education website that academic literary studies have changed:

Aikaisemminhan kirjallisuushistoriat kirjoitettiin ikään kuin kirjailijakohtaisesti, siis edettiin sillä tavalla, että ensin otettiin käsittelyyn F. E. Sillanpää ja sitten seuraavassa luvussa Pentti Haanpää ja niin edelleen. Tämä kirjailijakeskeisyys meiltä nyt lähes kokonaan kadonnut. Meillä on tässä suurena selittäjänä juuri nykyaikaistuminen eli seuraamme sitä, millä tavoin kirjallisuus on ollut mukana nykyaikaistumisprosessissa, ja myös sitä, millä tavoin kirjallisuus on nykyaikaistumiseen reagoinut. Onko se kommentoinut sitä kriitisesti, iloisesti, mitten nyt kulloinkin, millaisia näkymiä nykyaikaistuvasta maailmasta kirjallisuus on esittänyt.

[Previously literary histories were written as if in author sections, so that you would advance in such a way that first one covered F. E. Sillanpää and then in the following chapter Pentti Haanpää and so on. This author-centered way of thinking has now almost completely vanished. Here we have contemporary times as a great explanation or our society, how literature has been part of the modernization process and also how literature has reacted to contemporary times. Whether this is commented on critically, joyfully, however at any given point in time, what kind of views literature has presented about the contemporary world.]

Koskela sums postmodernism's importance up quite wisely here. Postmodernism will change the way literature is studied. Already literary studies have increasingly mixed with interdisciplinary studies in numerous other fields including feminism, cultural studies, and queer theory. This is reflected both in the way literature is studied and in the literature itself. Postmodern literature takes pastiche to new levels.

One result of postmodern literature's predilection for pastiche is that it appears cluttered by modernist standards. Postmodern literature often includes flourishes and embellishments from various eras. Critics of postmodernism have accused authors like Kjærstad, for example, of showing off because of his ubiquitous references to bits of knowledge from various fields. These references, however, are from miscellaneous factual embellishments. For example, Homo falsus is peppered with references to Sergei Nechayev and Greta Garbo's Queen Christina. Far from random, the Russian revolutionary and the Hollywood version of a Swedish queen were carefully chosen; a reader with the right background knowledge recognizes them as examples of people who cross-dress to escape, in Nechayev's case from Russian authorities, who wanted him in connection with a murder, and in Queen Christina's, as a temporary respite from her royal duties and obligations. This ultimately mimics the narrative situation of the text as a whole, which appears to have been written both by the male, salad-eating narrator, and the female Garbo impersonator, Greta. Through these allusions, Kjærstad suggests the possibility that the two narrators are not two different people, a man and a woman, but one person who sometimes dresses in drag.

By postmodernist standards, modernism seems dull. Modernism's relatively homogeneous style, without the excitement of metafiction or frequent interruptions of humorous references to everyday elements from the reader's life, comes off as boring to some readers. Modernist literature's subtle humor or, more often, serious tone can seem stuffy to a postmodernist. Finally, modernism’s stable, realistic world may appear uneventful to those more used to postmodernism's fragments of different, incompatible realities and changing ontological levels.

Postmodernism is sometimes criticized as "too American." While the movement may have started in the United States and then spread, the situation is far too complicated to draw sweeping conclusions. Wherever the theory is coming from, and a great deal of it certainly originates outside of the United States, postmodern literature is being written around the world, recognized as such by academics most everywhere, and commented on as such by critics globally. A Finnish family on a small dairy farm outside of Kuopio once forced me watch an episode of the Simpsons with them. And I never met anyone as devoted to Seinfeld as my Norwegian friends. If postmodern literature, by drawing in references to popular cultural icons such as the Simpsons, Dynasty, or Seinfeld, is too American, then that is because the Europeans themselves who pay to import and broadcast American popular culture are too American. And if anyone is seriously arguing that families on rural Savo dairy farms or small towns along the Sognefjord are too American, they need to reconsider what they mean by "American."

Both modernism and postmodernism have been criticized as nihilistic. In both cases, this is quite an overstatement. Specific texts or authors may be nihilistic, but modernism and postmodernism as entire movements are not. Modernists' eternal quest for a new grand narrative to fill the vacant center left by the collapse of previous grand narratives is evidence of modernism's lack of nihilism, not to mention the idea that modernist texts almost always have a unifying consciousness and that their puzzle pieces can be assembled to form a larger picture. Postmodernists are nihilistic in that they believe there is no universal objective basis for truth, but not at all in the sense that they believe life pointless and human values worthless. For they do not. Each of the five postmodern novels I will examine in this project demonstrates a subject in the process of creating itself, making him/herself human and moving to the next ontological level. In Kjærstad's Homo falsus, Jäntti's Amorfiaana, and Tapio's Frankensteinin muistikirja, the subjects literally progress from a character in someone else's story to become a person in their own right. In Hoem's Kjærleikens ferjereiser, an entire coastal community forgotten by the big-city bureaucratic government becomes real. And in Lie's Løvens hjerte, a timid, victimized woman becomes bold, and with the help of her contact with the fictionalized Louise Labé, goes on to live a more meaningful life as the author of her own destiny. This theme of creating and empowering subjects appears in many other postmodern books and is not compatible with the label of nihilism.

Finally, modernism has been criticized for dwelling overly much on alienation and postmodernism for being too lighthearted. While modernist literature does have a tendency to be somewhat darker and postmodernist literature more playful, this is hardly a reason to criticize an entire movement. These criticisms clearly reflect taste preferences rather than any great contribution to scholarship. Charles Jencks considers the moment in 1972 when the Pruit-Igoe housing project, widely recognized as unliveable, was imploded as the death of modernism in architecture. At least modernist literature never had to be blown up.