FROM HOMESTEADING

by

This story is dedicated to the men and women who immigrated from the European countries to the United States of America and homesteaded in the Midwest. Many, after difficult years of trying to make a living as farmers, moved to the Western states to begin their lives and dreams over again. A high percentage found success and became leaders and prosperous members of their communities. Most of the Scandinavians were "men of the soil" and made their new homes on small farms, often carved out of the dense woods of the Pacific Northwest.

A SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT

To my wife, Ayleen, whose encouragement

made this publication possible.

It was October 6, 1942 when I sped up the old Sunset Highway. I had traveled this road many times as I went to work in the lumber mill in Snoqualmie and at other times for pleasure. My concentration on getting to Snoqualmie was interrupted by the loud siren of the State Highway Patrol. I explained to the officer that I was hurrying to the Snoqualmie Hospital where my father had been taken after being injured in a logging accident that morning. After admonishing me to drive carefully, he permitted me to continue to the hospital and to my father.

Peter Erickson, who was born in Offerdahl, Sweden, April 6, 1884, was the third child in the family and was the second son. Custom dictated that the eldest son inherited the family farm and also took care of the parents. So Per, as he was known at home, thought many times of his future. He had to leave home to make a living and leaving home meant, for many, going to America. Such plans usually included making money in the U.S. and then returning home with money to buy a farm and be independent. This was the plan that made sense to Per. He had saleable skills that he had learned from his father, Eric, who was a well-known blacksmith and builder of water-powered sawmills. Logging was a common winter activity, while the spring and summer included farm work. Cattle were herded in the lush mountain meadows. Women in the family, including the younger ones, lived in the mountains in what was known as a "stuga," or cabin. Their responsibilities were to milk the cows and goats and make the butter and cheese, while the men put up hay which grew in the meadows. All this was done by hand--no machinery.

Mandatory military service was required of all young men in Sweden. So this delayed Per's plan to go to America, but there would be few expenses while in the army, and this enabled him to pay for his trip to the new country. Military service usually lasted for one year, but on-again-off-again hostilities with neighboring Norway meant an extension of Per's army life. His group was posted in the mountains that bordered Norway and Sweden. The location is not far from the main highway that goes from Ostersund, Sweden to Trondheim, Norway. Time and boredom was the way Per described his time in the mountain passes. Some diversion was available through marksmanship and skiing competition. He won a set of six gold-plated spoons as the company champion in marksmanship.

Negotiations ended the threat of armed conflict, and the two countries, arranged a peaceful solution to old problems. Per returned to his home and began serious plans for his journey to America. Concern for his welfare was tempered by the fact that two uncles had already emigrated to the United States: one to Fall City, Washington, the other to Minneapolis, Minnesota. His plan was to buy a train ticket from New York to Seattle, and then find his way to Fall City, a distance of approximately 30 miles. This he knew he could walk if no other transportation was available. Money was difficult to come by, and even more difficult to accumulate. While Per was working to save enough for his ticket to America, he also had to acquire the necessary papers that permitted him to leave Sweden. The minister had to attest to his character. Proof that he had completed his military service was obtained. So was an exit visa declaring him to be in good health. Per was classified as an "arbetaren" or "worker". Farewells were difficult because so many relations and friends had gone to the new country with promises to return, but were never heard from again. Some of this lack of communication was due to poor or no writing skills. One brief letter a year was not uncommon. Per left his home, his mother and father, two brothers and three sisters for a new unknown life in America. He did not know that he would never return.

Per's family in Sweden: a brother, Eric, and his family; a sister, Karin; a brother, Andrew; and his father and mother.

Per left southern Sweden by boat, for Liverpool, England, where he boarded a ship, the Virginian, on June 25, 1909. The ship landed in Quebec, Canada, on July 2, 1909. His classification on the passenger manifest was as an "emigrant- steerage" passenger. The accommodations were very crowded; many services were nonexistent. Families with little children suffered the most. Very little daylight penetrated the steerage compartment. The limited bathroom facilities were soon overflowing and smelling of diapers.

Steerage passenger service did not include food. His food package from home would last him until he reached Canada. Water was available for drinking when you could get it, and the smell, the noise, and the misery of the children drove Per topside whenever permission was granted.

The seven-day crossing was relatively smooth and Per suffered no seasickness. He was told that his ticket would take him by train from Quebec to New York. He found that a large percentage of the passengers on the Virginian were also bound for New York. He did not understand the language, but he followed those who seemed to know where they were going. The train trip to New York was uneventful, although the accommodations were minimal. The excitement of being in America tempered the inconvenience and the language difficulties. Arriving in New York City was an overwhelming experience. The passengers were told that if they were going west by train they should stay in the railroad station. Later they were placed in groups. Those going west by way of Chicago, Minneapolis and Montana were told to line up and buy tickets, and they were then directed to a particular gate where they boarded the train for their first trip across this new, big country. And big it was! Per said the train trip took days, and the vast open spaces were mind-boggling to those whose home country could almost fit inside Montana. Per mentioned that when the train stopped at the railroad station in Chicago, he felt the need to supplement his diet of hardtack and cheese. The station included a small grocery store. He looked at various foods for sale and finally selected a bottle of red-colored sauce. It reminded him of the sauce his mother made from lingonberries. When he was back on the train he opened the American red sauce and took one big swallow. One was enough, the red sauce was catsup!

As he traveled through Minnesota, Per knew he had a first cousin living in the northern part of the state. He thought, perhaps, he could stop and visit her on his way back to Sweden. He recalled, in later years, his impressions of the vast country he saw from the train as he made his way to the West Coast, eventually arriving in Seattle. Soon he was with his uncle in Fall City, where he was warmly welcomed. News from his home in Sweden was important, but frequently unavailable. Work was available in the mill town of High Point, which was located four miles east of Issaquah. There he met many men from his own area in Sweden called Jamtland. They encouraged him to apply for work in the woods. There, you could buck shingle bolts out of the brush and then to a horse- drawn sled. A shingle bolt was a block of old-growth cedar about four feet long and split into pieces large enough for one man to handle. This involved lifting, or bucking, this piece of cedar end over end and out of the brush and then loading it on the horse-drawn sled. Once the sled was loaded, it was then taken over the skids to the shingle mill. The skids were greased in places that involved a steep grade.

Shingle bolt logging--Per, second from the right--seated.

The shingle mill was located at the mill town called High Point. It consisted of a company store, a 12-room hotel, a church, the shingle mill, the main mill (or lumber mill), plus housing for families, and housing for single workers such as Per. A two-room school served the educational needs of the young and old. It was here that Per and other immigrants sought to learn the language of their newly-adopted country.

Per worked in the logging camps, as well as shingle bolt camps, for two years. He spent very little money on himself because his goal was to save enough money to go back to Sweden and to his family. When he had saved roughly three thousand dollars he left the State of Washington and traveled by train to Minneapolis where he visited with an uncle and his family. From the Twin Cities he took a local train called the Soo Line to northern Minnesota, where he visited his cousin, Brite Erickson. She was married to Nels Risen, who was homesteading in Pennington County.

Per--second from the left with friends.

The time of the year for Per's first exposure to northern Minnesota was in the spring. Everything was green and lush. He learned from his relatives that there were several 160-acre parcels still available for homesteading, including the 160 acres a little more than half a mile east of the Risen home.

Per decided to delay his return to Sweden long enough to claim 160 acres under the Homestead Act. This meant living on land for three years and making modest improvements such as adding a cabin. Per reasoned that he could sell his homestead after three years for the sum of $3,000, which was the going rate at that time. With this additional money he would then continue his journey home. After filing for the homestead, Per was one happy emigrant. He now would eventually own more land than was available at the home place in Sweden. The attitude was understandable when you relate it to the scarcity of tillable land in the parts of Sweden that Per called home.

The first task was to build a cabin that would provide him a place to live while he laid claim to the homestead. Logs for a small log cabin were available on his own land, so it was not many days before a home was a reality. It was not fancy, with about 100 square feet of floor space and no floor; a wood stove; a bed and some cupboards; and a small table with two chairs. That was his furniture. It was not long after the cabin was built and the outbuildings usable that the Northern Minnesota winters introduced Per to the contrast in weather from his first spring in Pennington County. Per related that the first winter in the homestead saw temperatures of minus 40º F and 50º F with the wind often accompanying the winter storm. It was not unusual for the temperatures on the inside to be only a few degrees warmer than the outside, with the snow drifting through the cracks in the log construction. I recall being told that after the family home was constructed, the first homestead home became the shelter for pigs that were raised for sale and for food.

With the onset of winter, there was little that Per could do to improve the homestead, so he sought employment. One of the jobs available was that of postal employee. For about $10 per month, he would make the 10-mile trip on horseback to a place called Wanke. He would bring the mail to the homesteaders on his way home and then deliver the letters that were addressed for delivery to the Homme post office, which was the home of the early homesteaders in that county. Per often related some of the problems he encountered as postal carrier. The weekly trip in winter was often one of cold winds and drifts. Winds and drifts of dry snow would often create whiteouts which would make visibility nil. He said that when they occurred he soon learned to trust his horse, which seemed to know the way home.

Per was a mail carrier for about six months. Now, however, he had responsibilities that demanded his time and eventually changed his plans. He met and courted the daughter of Peter Bjerkle who was the first homesteader in Pennington County. Julia, the eldest daughter in the family of 13 Bjerkle children, was soon in love with this young blond from Jamtland, Sweden, and they set a date to be married in the spring of 1912. The little cabin would not be satisfactory as the home for the new bride. Per enlisted the help of Nels Risen, who was married to Per's cousin, Brita. The first task was to select trees that were uniform in size and reasonably straight. The trees that were selected were cut down, trimmed and hauled by sled and horses to the site for the new home. The logs were cut to the proper length before they were hand-hewn into squares that were approximately eight inches. Care was taken to make the logs as straight as possible, so as to get as tight a fit as possible. The logs, once in place, were secured with wood pegs where necessary. They were made air-tight by trowling in a mixture of sand, cement and water between the logs. The extremely cold weather would sometimes cause the cement and sand to crack and fall out. When this happened, the ingenuity of the homesteader came into play. Manure from the cows was trowled into the broken spaces before it froze. It would quickly freeze solid and remain in place until it thawed in the spring and then was replaced with cement and sand.

Per and Julia were married in the Nazareth Lutheran Church in Hickory Township. They were the first couple to be married in the new church. Per had been one of the volunteers that helped build the first church in the homestead township.

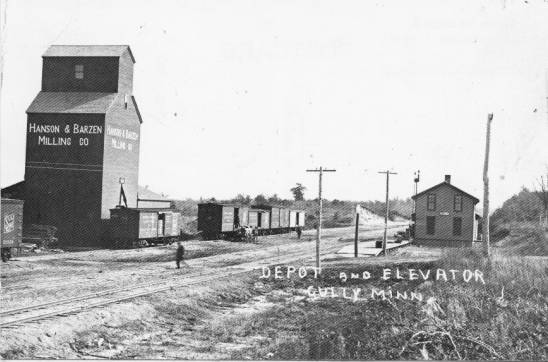

The newly-weds moved into the eventually completed two-story log house. A barn of logs was constructed to house the cattle. The cows had to be indoors during the coldest part of the winter. One of the few ways to get cash was to milk the cows and then sell the sour cream to the creamery where it was made into butter. Creameries were either privately owned or cooperatives owned by the farmers. One cooperative was established in Gully, Minnesota, a town 13 miles south of the homestead.

With the cows and horses, there was a demand for hay. The meadows on the homestead provided the pastures and the hay. Tons and tons of hay had to be cut by horse-drawn mower, then raked, allowed to dry, and put in piles called shocks and then piled onto the hay wagon. Some of the hay was stacked as close to the barn as possible. The rest, and by far the largest amount, ended up stacked in the fields where it was cut. This meant that a daily winter chore was to hitch a team of horses to a hayrack on sleds. About a ton and a half of loose hay was loaded and stomped into place on the hayrack. The hay in the stack would have settled and compacted so much that a hay knife would have to be used to cut the hay free so that it could be loaded. The haystack would appear to be a clean vertical cut across it after a serrated hay knife had been used.

The original log house on the homestead with mother and dad and three of the children; from left--Eddie, Magda and Stella

Children soon filled the homestead and Per and Julia were blessed with four girls and one boy. The boy was named Eddie and at an early age he would accompany Per for some of the farm chores. One such tag-along trip was to haul a load of hay for the cattle. As a five year old, Eddie felt he was helping when he "stomped" the hay in the corners of the hayrack. On one hay hauling trip tragedy nearly occurred. The load was almost finished and topped off about 10 feet off the ground when Eddie got too close to the edge of the load and fell to the frozen ground, striking his head. Eddie was unconscious until shortly before they arrived at the barn, but he recovered with no ill effects.

Though much of the homestead was grass meadows, some of the best soil was in the timber area. This involved clearing the ground of debris and stumps. No heavy equipment was available--only hand tools and a handmade stump puller. The stump puller consisted of a cast iron drum about one-foot in diameter and two feet high. The drum was mounted on an anchored base and turned on a heavy pin. The drum was then turned around by a horse attached at one end by a pole to the top of the drum. In this way, a cable was attached to the stump and, as the horse walked in a circle around the drum, the cable was wound tightly around the drum, thereby pulling the stump out of the ground. It was a slow and labor-intensive process but nevertheless hundreds of acres were cleared in this fashion by the homesteaders. I can recall a task at an early age: this was picking up small sticks from the area being cleared. It was a most hateful task because there seemed to be no end of sticks. A five-year old soon learned that work was as much a part of his life as play. At the age of seven you were assigned two cows to milk and I can also recall I was tied to a horse-drawn mower so as to keep from falling off the seat. Horses would walk along the uncut hay and when they got to the corner, they would step around the corner, and then continue. It was my duty to not touch the reins but just to raise the cutter or sickle bar when the horses made the turn. This I did by pulling back on a tall bar. I was proud and pleased to be able to help. Dad was in the next field making hay, and I'm sure keeping close watch on my progress.

Another chore that the young ones on a homestead had to do on a regular basis during the summer was to build smudges for the milk cows in the barnyard. Building a smudge, or smoky fire, consisted of building a small fire with dry twigs and once it was burning to cover the fire with dirt from the barnyard. We would build four or five smudges in the barnyard and leave them while we went to the pasture about a mile from the house. We would open the gate leading to the north pasture and the cattle, usually waiting at the gate, would head for home without too much urging. Milk cows would head directly to the canopy of smoke created by the smudges in order to get relief from the flies and mosquitoes. When we went to bring the cattle home we would arm ourselves with leafy switches to keep the mosquitoes off our faces ... the northern part of Minnesota which is known for the water and lakes, is also known for its mosquitoes. There were no sprays available in those days to fight the hordes of mosquitoes. Cattle suffered from flies and mosquitoes and would get relief from the smudges that we built. A smoky cover had a peculiar odor, not unpleasant, and young farm kids never forgot it.

During the summer months, the cows were milked while corralled in the barnyard. The milk was separated and the cream stored for shipment and the skim milk fed to the pigs and young calves. No electricity was available for many years, so the only power available was either horses, stationery gas engines, or wind power. The chore of pumping water was another chore for children, and was eased a great deal with the installation of a windmill. This was a great help when you had to provide water for about 100 animals, as long as you had any wind to turn the big wheel. When there was no wind, it was back to the pump handle. Wind and the windmill would be a problem when the wind was too strong. My dad taught me, at a young age, how to trip the mechanism so that the edge of the windmill would face toward the direction of the wind. This knowledge was used on one occasion when the telephone grapevine reported that a hailstorm accompanied by high winds was headed in the direction of our farm. My father was not at home, so mother asked if I could "set" the windmill. I replied "Sure," and with the confidence of a seven-year old climbed the windmill tower and set the windmill so that the storm would not damage it.

My father, Per, acquired an additional 160 acres, not adjacent to the original homestead, but located about one mile north of our farm. One clear, cold winter day while playing outdoors with my sister, I decided to find my father. I knew that he was cutting wood in the "northland," and all I had to do was follow the sled tracks. The snow was as deep as my five-year-old height, but by walking in the sled tracks I could make it with considerable ease. In the meantime, my older sister, Magda, had run home and sounded the alarm. My mother could not leave the two babies to look for me so she called a neighbor--his name was Risen--and asked if their son, Everett, could come on his horse and try to find me. Mother had horrible visions of my being attacked by timber wolves. Their howls at night indicated that there were plenty of them, and there was just cause for her concern.

In the meantime, I was continuing in the sled tracks and looking for my father. I finally heard the noise of his ax that he made while cutting timber. Needless to say he was surprised to see me. I told him I was hungry and he reached into the pocket of his heavy coat and handed me one of his sandwiches. I recall that the sandwich was frozen solid but it still tasted good and satisfied my hunger. While waiting for my father to finish cutting and loading a load of logs, I found some beautiful red bark willows. They were the kind that turned a beautiful bright red when the weather was very cold. I had a handful of these red switches when Everett Risen showed up riding his horse. He said that he had followed my tracks in the snow and was able to find me. My father lifted me up on the horse so I could sit behind Everett. When Everett noted my fist-full of red willows he said, "You had better bring those with you, I'm sure your mother will want to use them on you." With those prospects in mind, I was not about to furnish the weapons so I opened my hand and let the red willows fall to the ground.

Working in the woods was a winter activity for my father. Not only did my father cut wood for the heating and cooking for our home, but he cut wood for sale. Farmers, who had no timber on their farm, would pay my father $20 for a load of wood, and some load that would be. The wide-bunked sleds would be pulled by two teams of horses. The loads would be eight-feet wide and up to ten- feet high. Care had to be taken to have the horses move the sled a few times during the loading. In the cold weather the sled runners would freeze to the ground and the loaded sled could not be moved. This happened more than once. Sometimes the wood buyer would not listen to my father's warning. They would not believe that friction would develop heat in the metal runners while they were bringing the sled to the farm and that, in turn, would melt the snow and freeze the sled if it was not moved.

Another winter activity was cutting and storing ice for summer use. Farmers who stored ice would get together when the ice on the Clearwater River was about two-feet thick. They would meet where the bridge crossed the river and join forces to cut and load blocks of ice measuring one foot by two feet by two feet. The ice was hauled home to the icehouse. The icehouse was a small log house where the ice was stored with sawdust as an insulator. The ice would keep until the latter part of August and provide ice for delicious homemade ice cream.

Winter transportation was by horses and sled. Per made periodic trips to the town of Gully in the winter to take a load of grain to be sold or ground. It was an all day trip. On one occasion I was permitted to go to town with my father who was having some grain ground for feed while he purchased some grocery items. The trip to town was uneventful and not too cold. I recall getting my first banana from the grocer and having to be shown how to eat it.

Depot

and Elevator - Gully, Minnesota

When all the errands were completed, we headed home. The road was 13 miles to our home and was straight north from the town of Gully. Before we had gone very far the wind began to freshen and the temperature dropped. Even though we were warmly dressed, my father made me get off the sled and walk behind the sled. The idea was to keep me warm by exercising. I would walk for a while and then ride for a while until I would start getting cold. We finally got home with the thermometer registering minus 15 degrees Fahrenheit.

I mentioned the road north from Gully, but I should have defined it as a dirt mound with ditches on both sides. There was no gravel, so the wet seasons produced deep ruts. The winter roads, though troubled with snowdrifts, were actually the best. There was little county money for roads and, as a result, many of them were sadly in need of repair. There was a road tax levied on all property owners. This tax could be paid for by working on existing roads or building new roads. I can recall going with my father when he "worked off" his road tax. The men were building a new road with horse drawn fresnos. They would scoop the dirt from the ditches on either side and then dump it on the road. The fresno, for those who are not familiar with horse drawn equipment, is simply a three-foot wide scoop with handles. The fresno is guided by the teamster who holds the scoop at the proper angle to fill the scoop. When it is filled he raises the handles to dump it when he arrives at the appropriate place to get rid of the dirt. There was also a great deal of road building and repair work done with wheelbarrows, shovels and rakes by farmers who lacked the heavier equipment such as the fresno.

Roads, or lack of them, delayed the acquisition of automobiles in that part of the country. The roads that did serve the early homesteaders were seldom more than ruts and mud that made the narrow tires of the early automobile a real challenge.

Per purchased his first automobile in 1919. It was a shiny black Model-T Ford touring car, and one of the first automobiles in the county. It was not used a great deal in the winter months and, as a consequence, it spent most of the year on blocks of wood. This was done to keep the tires from getting a permanent flat on one side.

A mention was made of the ruts in the roads. It was often said that you did not need to know how to drive--all you had to do was choose the right rut and you would get home. One incident further emphasizes the impact of grooved roads or ruts. Per and his family were returning from a visit to the grandparents. It was dark and the Ford magneto lights were always weak, but this evening they were bright enough to show a large mother skunk and three half-grown babies walking in a row in the rut that our car was in and going in the same direction. Dad waited, hoping that the mother skunk would get out of the rut when bothered by the lights and leave the road, but this was not to be as she waddled down the road. Finally, dad gave up waiting and drove down the road hitting the little skunks first and as a result the mother skunk sprayed the car liberally before the car finally stopped her. Needless to say the event stayed with the Ford for a long long time.

When crops were poor because of rain or when prices were low it was difficult for the homesteaders to have any money for taxes, clothing, food and other necessities. One neighbor established a sawmill to cut lumber for boxes which were sold for egg crates and apple boxes. This activity brought some money to the area to those who brought timber to the mill or worked for the mill owner.

Per invested in blacksmithing equipment that included an anvil, a forge, and an assortment of hammers and chisels, and leather bellows that provided the air that entered the forge. He had learned his blacksmithing skills from his father and it proved valuable as a source of much needed extra income. As a young boy, I had the chore of operating the bellows which I enjoyed for a short period of time and then it became work.

A county school called #9 was built early in the homesteading of Pennington County. It was a small one-room building with a coatroom on one side. The school could accommodate 20 students, but there were usually 12 to 15 in attendance. All eight grades were taught and all students would hear the recitation of other classes as well as their own. No indoor restrooms were available and toilet needs were served by outdoor toilets. A woodshed served to store wood that was supplied by parents for the stove in the classroom. The teacher had to arrive at the school early enough to build a fire and get the classroom warm by the time the students arrived.

All students walked to school--some as far as three or four miles. On an extremely cold day they didn't come to school or when snow had drifted they would often times stay at home. Sometimes parents would bring their children to school by horse and sled. One neighbor enclosed a lightweight sled called a cutter and installed a small "pot bellied" stove for heat. He would transport his two children, my two sisters and me to school on the coldest days. This could be described as the forerunner of the modern school bus with runners.

One of the chores at school was to take the school water bucket to a nearby neighbor and get water. This farm had an artesian well where the water flowed in a continuous stream and as a consequence never froze. It was a welcome break from the classroom routine to be asked to accompany another student to get water for school use.

School was generally a pleasant and rewarding experience except for one frightening experience. All eight grades were represented and some of the students were 16 and 17 years old. One boy in particular was 17 years old and should not have been in the school. He was mentally retarded and tended to be abusive with the younger students.

One morning he decided to pick on me and this resulted in my leaving the school and hiding behind a large haystack. When I felt reasonably safe, I peeked from around the haystack with intention of returning to school when the other students were in the classroom. Instead of seeing that it was safe to return, I saw the entire student body, with the exception of my sisters and Aunt, headed in my direction. When I saw the group was led by my tormentor my immediate decision was to head for home. The normal route was through the woods on a fairly good pathway, but this day fear told me to take my shortcut that I frequently took to get home ahead of my sisters. This route was across a swamp where I had learned to know which tufts or grass islands would support me and where to avoid the soft muddy ones. As an eight-year old I had run this trail often and, now, inspired by fear, I was hollering as loudly as I could. I looked back and saw a dozen students behind the school bully. Some were dropping back to return to school, but five or six continued to pursue me, for they had been told by the teacher to bring me back to school

My fear kept me moving toward home and the short-cut I had chosen slowed the pursuers, so I was able to reach home before these school-age vigilantes. My mother immediately knew this was no school prank or minor incident. She met the students at the door where they demanded that I be handed over to them so that I could be returned to school. Mother, brandishing a broom, told the students to go back to school and that Mr. Erickson would see the teacher that evening.

A special school board meeting was held that evening and, as a result of the incident, the 17-year-old boy was dismissed from the school and later institutionalized. The teacher was admonished to refrain from sending all the students away from school for any purpose except if the school building caught fire. My grade school friends who still remember the incident have often said that I could be heard over the entire county as I screamed with fear of my pursuers.

The lack of medical facilities, except for one doctor in the small town of Gully, was a genuine concern for all the early homesteaders. The distance to the Doctor's office was 13 miles from my home. Most illnesses were cared for by home remedies. Nearly all children were born without medical attention, and their mothers were attended by midwives. Many families were left motherless as a result of complications that often could have been averted with proper medical care in a hospital.

The seriousness of a medical emergency was demonstrated when my father became ill with severe stomach pains. He finally went to Gully to visit the only doctor available. The doctor said he had appendicitis and should get to Minneapolis as soon as possible. My father had to ride his horse 13 miles to his home so he could tell my mother what had to be done and also make arrangements for help with the chores while he was gone. He then rode his horse back to town, another 13 miles, and made arrangements to board his horse. He then took the local train to Minneapolis--a distance of 200 miles. After arriving there he checked into the main hospital where arrangements had been made by the Gully doctor.

The operation was successful and timely. The doctors in the hospital told him that he was fortunate because the appendix was close to rupturing. If this had happened at home or enroute, his survival would have been questionable. As soon as my father was able, he took the train north to Gully and, after paying for a week of board for his horse, he headed the 13 miles home and to his family. Everything was fine at home and he was thankful for the good fortune and good neighbors who had helped in his absence. The experience further emphasized the isolation of the homestead in the event of a medical emergency.

Another incident that called for help that was not available was when one of my sisters was born with a "Club" foot. She literally walked on the outside of one ankle. The closest orthopedic hospital was in Minneapolis and this ruled out any early help.

My father, with his blacksmithing skill, fashioned a hinged brace that was adjustable. When my sister began to walk, he purchased a sturdy pair of shoes for her and then attached the brace he had made. When he first attached the brace it would lie almost flat on the floor, but as the weeks went by he kept tightening the leather strap that went from the brace around her leg. This gradual pressure continued for a year when she was able to walk without the brace and the foot had only a slight curvature to indicate that there had been a problem. During this homemade orthopedic correction, my sister never complained except when we played outdoors. When we played hide and seek, she said that the brace made so much noise that she could not sneak up on the others in the game and this was unfair.

Years later, my father took my sister into the Children's Orthopedic Hospital in Seattle to determine if any additional correction was needed. They assured him and congratulated him on the brace he had made and on his foresight in beginning the corrective treatment when he did. They said that, except for chrome plating and some other minor refinements, their corrective brace would have been very similar to the one he made. My sister still has the brace as a memento and as a reminder of her good fortune to have a father with the insight and ability he had.

My sister's foot brace built by my father.

Life for homesteading families was difficult enough without the events over which they had no control. In 1919, a very serious strain of flu hit the United States. It did not miss Pennington County. Whole families were struck by the epidemic for which there was no vaccine. It seemed young boys and men were hit the hardest. One family, a neighbor, had a mother, two young daughters and three teen-age boys and they all were stricken. The boys and the father died while the mother and the girls survived. This was generally the pattern and many farms were abandoned when the men in the family died.

My father and one next-door neighbor were the only men in our township who did not get the flu. As a result, they spent many long hours going to the neighbors to feed the livestock and to milk the cows. It was not their intention to save the milk but to save the cows. If the cows had not been milked they would have developed milk fever.

My father and mother had many discussions about the future and possibility of leaving the homestead. My father visited other farms that were for sale and all of the ones he visited were south of Pennington County and in areas that were less plagued with floods. Many years later, the Federal Government drained and straightened the Clearwater River and the Red Lake River. This allowed the drainage of thousands of acres of land that had been previously subjected to annual flooding, This same area today has some of the best farm land available and is called "Black Gold" by some.

One plan that especially interested my father was to move to the State of Washington where he had worked when he first came from Sweden. This idea was rejected at first by my mother. This was understandable in that her family was all in close proximity to the farm. However, by the spring of 1924, it was decided that my father should go to Western Washington to look for a possible home site and the prospects of employment. By this time two of his sisters had come to the United States. One was married to a farmer in Saskatchewan, Canada and his oldest sister lived in the mill town called High Point, Washington.

My dad found that he could find employment in and around High Point, and then began looking for a home site. He wanted land that he could improve and would eventually care for a few milk cows and some chickens. It was his plan to work full time and then take care of the farm in the mornings, evenings, and on week ends.

This was an ambitious program, but one that was followed by many immigrants like himself. They owned and lived on 10 or 20 acres, raised cattle and chickens and worked for wages either in the logging industry or in construction. They were known as "Stump Ranchers".

Dad found a 10-acre tract that was four miles east of Issaquah, Washington, a mile away from High Point. It was a rectangular strip that lay between the Sunset Highway and the Northern Pacific Railway. The land had a small amount of cleared land, but most of it was covered with alder, vine maple, and stumps from the early logging and brush. He cleared an area in about the center of the property and close to a spring that became our water source in the early years. Here he began the construction of a two-room cabin with plans for expansion. The framework, roof and walls were finished and he was installing the windows when events beyond his control would force him to board up the cabin and go back to Minnesota. He had received a telegram from my mother stating that my oldest sister, Magda, had pneumonia and was critically ill. Dad got home as quickly as possible, which in those days was by railroad. My sister recovered and my parents made plans to have a farm auction and then move to the State of Washington where the first boards for our new home were already in place.

A farm auction takes a great deal of hard work and planning. Decisions have to be made with the counsel of the auctioneer, as to how items should be grouped. For instance, should the blacksmith shop be sold as one total package or should bids be asked for individual items each, such as the anvil, the forge and the bellows? A decision was made to bid the items individually which proved to be wise because many farmers needed just one or two of the items to finish out their shop equipment. There were about 100 chickens and they were sold in lots or crates of 25. It was my responsibility to keep water in each of the crates by siphoning water from a bucket using a hose. It was difficult to concentrate even on this limited responsibility because there was so much activity and so many people that it was very easy to become sidetracked.

Farm equipment was checked and painted when necessary and all the livestock was brought in from outlying pastures and placed in appropriate barnyard areas where they could be seen by the potential buyers and also be there for the auction.

A farm auction was a social event for the farm families from miles around. Most auctions had little to attract the women, but a moving auction, where everything but clothing was on the block, was a special event. Dishes, cooking utensils, fruit jars, and silverware were all under the auctioneer's gavel and the women responded. Even then, many came for the visiting and socializing that was possible.

The sale attracted entrepreneurs such as the candy, sweets, and tobacco salesmen who arrived with their attractive wagons and opened for business in the farmyard. The arrival of the "Candy Man" drove me to desperately explore ways to get a few cents for the purchase of candy. My dad was too busy to approach, and my uncles said that they had no money. At the height of my anxiety I remembered that I had 11 gopher tails for which I could get a bounty of three cents per tail from the bounty man. I had already spotted the bounty man so the problem was to find my little snap purse where I knew the tails had been stored. I finally found it, after unpacking much of mother's careful packing for our move to Washington, and ran to find the man with the authority to pay me 33 cents. I showed him my purse and he asked me how many gopher tails I had in there. I said "11" and he started to look more closely and he noticed, as I had, that there were small white wiggly worms in the coin purse. It was apparent that I had not cured the gopher tails before I stored them and as a consequence they were very much alive with maggots at that point. He gave me the 33 cents without counting the tails. With this amount of money I was popular with my sisters and thought that auctions were a great event.

Food for all who came to the farm auction was provided in the form of sandwiches that had been placed in paper bags. Coffee was also available. This was a heavy chore for my mother who also had help from neighbors and relatives.

When the last car and farm wagon left at the end of the day, an eerie quiet settled on the farm. I could hear none of the farm noises: the chickens, the cows and calves, and their calls and the cowbells. Another evening sound was the cream separator and its high-pitched hum as it wound up to speed. It, too, had gone under the auctioneer's hammer. Even the pump and the windmill would be gone as soon as the new owners could dismantle and remove them.

We finished packing and loading the Model T and drove to my grandmother's farm which was about a half mile from our home. We were to stay there for a day or two and say our farewells and tie up any loose ends left over from the sale.

The next morning we awakened to learn that someone with scarlet fever in its most contagious stage had been present at the sale. My mother and four sisters were all ill with the dreaded fever. My grandmother had some medicine left from a bout of scarlet fever in her family the year before. The medicine helped and it was not necessary to call a doctor which would have resulted in at least a six-week quarantine.

It was already late in September and any further delay made an automobile trip over unknown mountain passes a real hazard.

We left my grandmother's home after one week delay and drove 20 miles to visit two of my mother's sisters. Enroute, my father found that the loaded Model T needed overload springs to keep the tires from rubbing the fenders.

We had planned to stay one night at my aunt's but that was not to be. The next morning I was ill with the fever. I can't recall ever being more ill than I was with scarlet fever. The fever broke in five days and my dad felt we had to be under way or abandon the trip. The fact that we had to sit quietly for hours on end perhaps freed us from complications that could arise from too much exertion too soon after having the fever.

Having driven only in the flat areas within the radius of a few miles from our homestead, the first hills that my father encountered in North Dakota were frightening. On one fairly steep grade he had mother and the five kids get out and walk and he would meet us at the top. The exercise, at least for the kids, was a welcome change until my dad questioned the ability of the loaded car to go down the grade with safety and, you guessed it, we walked down the grade as well. By this time I was convinced that we were going to have to walk to Washington. Fortunately, my dad developed more skill and confidence. The Model T proved to be better able to climb hills, but the brakes would prove to be less than effective in stopping the car as a later story will attest.

Traveling across the country in the early twenties was a far cry from the amenities found in today's travels. Very few, if any, motels were available. There were cabins that featured a double bed and a shed or carport for one car. There were no kitchen facilities in those cabins and the bathroom facilities consisted of a washstand, a bucket of water, and a washbasin. The toilet accommodations consisted of facilities that we were all too familiar with from experience on the homestead.

Our search at the end of each day was for a campground. Most towns had a campground where there was a water pump and, in rare instances, a water faucet. Most of the campgrounds had one or more picnic tables. Because we were traveling in late September, there was very little competition for space and most of the time we had the camp space all to ourselves.

The first chore was to erect the tent which was supported on one side by the automobile. The back corners were held up by two-foot stakes that were anchored by stakes in the ground and then connected by a short piece of rope. We slept on the ground with blankets on the ground and on top of us--no air mattresses or sleeping bags. As kids we could sleep anywhere, but I can well imagine the discomfort experienced by my father and mother on that hard packed ground. This was attested later when my dad visited a neighboring hayfield after dark and removed a generous armload of hay to soften the rock-like bed that we had endured. It did improve our sleeping accommodations for one night but unfortunately the hay that my dad had "borrowed" was a grass called cheet. The heads or seeds of cheet have a series of barbs or hooks that enable each seed to crawl into the blankets and our clothing. We were picking and scratching for the rest of the trip to Washington.

Cooking consisted of coffee for my parents, and, for all of us, oatmeal for breakfast. This was prepared over an open fire usually bordered by rocks. A blackened coffee pot and a kettle were the cooking utensils we carried. Lunch and dinner usually consisted of sandwiches that had baloney or cheese as a filler. We seldom stopped for lunch except to retrieve the canvas water bag that hung in front of the radiator. The air moving across the dampened canvas surface kept the water cool even on the warmest days.

Paved roads were only in some of the larger towns and then were limited to the city limits. All other roads were gravel which was a traveler's nightmare, considering the quality of tires that were available. A day did not go by without at least one flat tire and many days were interrupted with three flat tires. My dad carried four spare tires and in this way he could patch the punctured tubes in the evening after we had stopped for the day. Air was provided by a hand pump and lots of perspiration.

A modern day automobile can cover 500 or 600 miles in a day of travel. Granted the roads are much superior and the automobiles are a far cry from the Model T Ford with tires that were 30 inches in diameter and 32-inches across the tread. The best mileage we could make in a day was 200 miles, and usually it was closer to 100 miles.

As we crossed Montana and started to ascend the Rocky Mountains, my dad expressed real concern and prayer for favorable weather. Fortunately, no snow fell in the mountain passes but the mountains would take their toll nevertheless. It happened after we had driven through Wallace, Idaho and my dad was convinced that we needed new brake bands and reverse bands put on the Ford. The brake bands were worn out from coming down the steep grades of the Rocky Mountains. The reverse band, which was used when the brake bands were worn out, was down to the point of doing little or no good in stopping or slowing the car.

My dad stopped in Kellogg, Idaho to get information on the road conditions from Kellogg to Coeur d'Alene. He was told that they were fine which was a gross exaggeration in that the Fourth of July Pass, as it was called, was a notoriously bad stretch of road. Nevertheless with a good road report, my dad elected to go to Coeur d'Alene where he believed he would get better service because of the size of the city.

About 20 miles out of Kellogg we came to a detour that was rough and narrow. As we crested a rise in the temporary road, my dad saw that the road at the bottom of the grade was blocked by cars and a large truck. He tried to stop the Ford with what was left of the reverse band, but we continued to roll. In desperation, my dad crowded the Ford into the road bank hoping to stop it. Instead, the car climbed the bank and rolled over on its side. The crash, as the windshield broke, brought the occupants from the bottom of the hill to our rescue. They righted the car and blocked it to keep it from rolling, and then checked to see if anyone was hurt. Fortunately no one was injured. The rescuers tossed the broken and torn top over the bank which my dad quickly retrieved. He had used the deep padding around the edge of the top as a safe place to carry extra money. Eighteen years later, while disposing of the remnants of that original car top, he found one of the large sized $20 bills that had been secreted in the barn throughout the Depression years when $20 would have been a gold mine.

When the scattered belongings were loaded, including the damaged top, we continued on to Coeur d'Alene. There was no windshield, and to add to our miseries, it started to rain. As darkness approached we still had to skirt Lake Coeur d'Alene, which, at that time, was a narrow, cliff-hanging road with the dark lake directly below us.

We finally arrived tired, hungry, and shocked from our experience. We drove to one of the better campgrounds that we had encountered on the entire trip. The rain continued as dad struggled to erect the tent which had now lost one side of its support through the loss of the car top. The tent was finally put up though a bit tired, and it enabled the family to get in out of the rain. My dad had to dig a trench around the tent to divert the rainwater that was soaking the bedding.

The next two days were spent getting the car repaired, drying the blankets, and exploring the camp area. Dad told us that if everything went well we should be at our home in Washington in two more days.

Traveling across what was to become our home state, was a revelation to a farm family from Minnesota. The vast rolling wheat fields that had been recently harvested were amazing compared to the farm that we had recently left. My dad stopped the car to better observe a combine that was pulled by 16 teams of horses--all controlled by one teamster. One "header man" raised and lowered the header so as to retain a uniform height of cut.

We crossed the Columbia River at Wenatchee and planned to stay there in a campground. Before we arrived at the stopping point, we saw apple orchards in every direction. They had a bumper crop and low prices. This was before the modern day "controlled atmosphere" storage facilities. For youngsters who were accustomed to one apple a year at Christmas time, this was Heaven. One year, my dad was responsible for purchasing the annual box of apples for the church Christmas celebration. The box of apples was stored upstairs at our home and we were sternly admonished not to touch the apples. I can remember asking my dad if we could smell the apples. He gave his approval for this as long as we did not touch. From one apple at Christmas time to piles of red Delicious apples with signs saying "Help Yourself" was almost too good to be true. Needless to say, we did help ourselves to apples. Our first full day in Washington had been a memorable one. We camped alongside the Wenatchee River and started early in the morning for Blewett Pass. The gravel road had a reputation of being the most difficult of the mountain passes. It climbed swiftly with switchbacks, tight curves, and turnouts. The turn-outs were necessary since the pass was essentially a one-lane road.

Shortly before we arrived at the summit, the Ford stalled. My dad backed into a turn-out and had me get out of the car and block a wheel with a large rock. After a few minutes' delay, he started the car and continued to the summit by backing up the rest of the way. The 1919 Model T had the gasoline tank under the front seat and if the level of gasoline dropped to the one-quarter mark it would not feed the fuel to the carburetor by gravity flow when you were climbing a steep grade. When we arrived in the town of Cle Elum, my dad had the gas tank filled for our trip over the Snoqualmie Pass. This pass was not paved in 1924, but the traffic was limited and no special problems developed.

Crossing Snoqualmie Pass gave me my first look at the large old growth timber that was to become a vital part of our lives in the years to come. It was late in the afternoon when my dad stopped the car and opened the barbed wire gate to a lane that led us between dense trees and brush. We drove a short distance then made a right turn and there was the home we were to know for many formative years. Surrounding the two-room cabin were mounds of brush that had been moved to make room for the building.

Our early home on the Stump Ranch.

We unloaded most of our belongings and placed them in the cabin. mother then cleaned us as best she could in preparation for our first visit to my dad's sister and her family. It was dark as we drove up the grade to my aunt's home in High Point. We drove by a huge bonfire of slab wood and sawdust from the shingle mill.

My aunt told me years later that we were a tired looking bunch when we arrived. She said that the trip had been particularly tiring for my mother. Finally arriving after 13 days was a relief in spite of the work and hardships that lay ahead.

The two-room cabin was far from ready for occupancy. The chimney had to be installed and the inside ceiling, and finished floors had yet to be put in place. My dad spent long hours doing the carpentry necessary before we could live in the house. My folks had to buy a stove, the furniture that was needed, and other items that were necessary for housekeeping. They found a leather hide-a-bed that served as a davenport and could be opened into a double bed. it served well with the multiple use that was needed. In addition, they purchased a used double bed, a table and chairs.

Within a week we were living in our modest home and adjusting to some primitive conditions that we knew would get better. As children, we would help by carrying water from the spring that was our water source for several years. The spring was also our refrigerator where mother would put jars of fresh milk in order to keep them cool.

We were about a month late for school, so one of the priorities was to enroll at the High Point Elementary School. This proved to be a traumatic experience. Our dialect from the Scandinavian Midwest was different and some of the students mimicked and teased us. This soon passed and we were assimilated into the milltown junior population. Because we were late enrolling for school and perhaps, because our school in Minnesota did not have the same standards as in Washington, we were almost a grade behind where we should have been scholastically. My teacher, Miss Learsted, bless her heart, talked to me about the benefit of being at the top of my class, rather than the bottom where I was. It was not without tears, but I agreed with my teacher and I have blessed her many times for her concern and her insight.

The house was livable, but far from finished. An additional bedroom had to be added, but before that could be undertaken, a barn had to be erected to house the two milk cows that my dad had purchased. It meant that when we came home from school we had to herd the two cows alongside the highway where they could find green grass. We also took them to a recently logged area near our home on Saturday so they could graze all day. In the spring of the year, our herding responsibilities permitted time for some digressions. One was to clear a small patch of ground and plant radish seeds. We did this in several places so that later in the spring we had fresh radishes to eat. Not only were the radishes delicious, but it gave us something to do during a boresome day-long chore.

My dad went to work in the logging industry shortly after we settled into our new home. In the spring, summer, and fall there was enough daylight at the end of the day so he would come home to clear some land and prepare the soil for crops that would be fed to the cows. This was hard labor and labor intensive work and all by manpower. It seemed there was always a fire burning in a brush pile at our home. Once a fire was well started it continued to burn even though it was raining. Large, old growth fir stumps were too large to be dug out or chopped out. The stumps could not be dynamited because many were too close to the house. The only solution was to dig a hole under the stump and then build a fire under the stump. This worked well with fir stumps since they were usually impregnated with pitch. When they were hot from the fire the pitch would begin to run and would feed the fire. The problem was that the fire required continuous feeding, but you could get rid of a lot of brush that way. This was one of my chores as soon as I got home from school.

Before long, the need for some kind of power to clear land and plow the field was deemed imperative. My dad learned that the Benz Spring Company of Seattle sold the cast metal parts that could be used to convert the Model T Ford into a tractor. After purchasing the tractor parts for the conversion, he delayed the start of the conversion project. I did not know until years later that he was reluctant to begin cutting on his first car and the automobile that had brought us from Minnesota to the State of Washington. He finally relented and proceeded to cut and weld until the old Model T began to look like a tractor. It had large cleated rear wheels with regular cast metal tractor wheels in place of the front wood wheels and tires. The drive or power came from a pinion or gear on the differential that meshed with a large gear bolted to the rear tractor wheels. The gear ratio was forty to one, and, as a consequence, did have considerable power. We used this "Tractor" for a number of years for many of the chores found on a "stump ranch".

My dad discovered there was a demand for logging that required horses and skid road logging. Sleds were about 24-feet long, made of 3" x 12" fir runners. The runners were strongly cross-braced and cross bunks were placed on which the logs could ride. The runners which wore out and needed frequent replacements were made of dogwood. A tree about four inches diameter and straight was selected and then split down the middle. Each half that was placed on the bottom of the runners was secured with round inch-and-a half diameter maple pins. A hand auger was used to drill the pin holes.

Loggers, who were on their own and their own bosses, usually contracted with the timber owner or mill company to move the timber for so much a board foot. In one instance my dad contracted with the High Point Mill Company to remove a stand of old growth timber that was not accessible by the use of the larger steam donkeys.

The horses used for horse logging were large, raw-boned animals that had tremendous pulling power. They were not any special breed-just large, strong and with plenty of endurance. I can recall going with my dad to the horse sales and visiting the auction houses in Seattle. The horse barns were located in the area now occupied by Benraoya Industrial Park.

There were hundreds of horses to choose from and my dad and uncle finally settled on two of the biggest animals. After dickering for a set of harnesses that would fit, we headed to home with my uncle and myself in the back seat of the Model Teach of us holding onto the halter and leading the horses slowly from Seattle, through Renton, and on up to Issaquah. We trailed the horses on the Sunset Highway and then through Issaquah and to our home. We arrived at the barn before dark and with sore arms from hanging onto the halter that was attached to one big horse.

Logging with horses involved road building so as to have the fewest up grades, some flat areas, and mostly gentle down grades. The flat areas, and especially the up grades, required properly spaced skids that were dug into the edge of the road to keep them from moving. From the curve side of the road, skids were set at an angle to serve as sheer skids to help direct the sled and keep it on the road. On the flat and upgrade areas, one person would follow the sled and, on its return to the timber, the follower would dab grease on the skids where the sled runners made contact. When I was not in school, greasing the skids was my job. I always enjoyed being permitted to accompany my dad to the logging operation and see, first hand, the large fir trees being felled. They were bucked or cut to 24-foot lengths for most of the trees, and much shorter for the larger logs that measured three feet or more in diameter. They were skidded from their place where they fell to the landing. The landing consisted of two logs that were supported on one end by a series of cribs or stacked short logs to bring the two logs up to the same level as the sled. The other ends of the logs were at ground level because the location of the landing was usually at a place where there was a slight grade or slope.

Getting the logs from the tree stumps to the landing involved the horses~ blocks and cable; and a great deal of work. Often, one end of the log was "sniped" or beveled to help it over obstructions. Once on the landing, the large logs, where a load was one log, were supported at the outer edges of the bunks by two small logs. Once the load was in place, it was secured to the sled by chain and locking chain clamp. The teamster then sat or stood on the large log and guided the horses down the skid road to the main highway landing where the logs were then off -loaded to the landing and eventually to a truck that hauled them to the mill. Needless to say, only choice logs were brought out of the woods in this fashion. This method of logging proved to be profitable for my dad and this was fortunate in that he had many expenses such as adding two bedrooms to the house, building a chicken house for 100 chickens, plus the cost of feeding and clothing a large family. In addition, my mother became seriously ill and required hospitalization and a major operation.

When my mother returned from the hospital, my dad set about to bring electricity to our home. The power company refused to run the power for a distance of one-half mile from the transformer to our home, but they would let us hook up to the electrical source if we ran the wire at our expense. This is how we first got electricity and our first appliance was a Sears Roebuck Kenmore washing machine.

This eliminated the back-breaking chores of washing clothes on the scrub board. Two ceiling-hung light cords with a single light bulb at each location was our only other use of electricity. The voltage drop was too great over the distance from the transformer to permit additional use. This limited lighting was such an improvement over the kerosene lamps that we never complained. Incidentally, the power company owned the power line to our home, even though we had paid for the wire and the installation. It is a small wonder that my dad was a strong advocate of the public utility district that pioneered bringing electricity to rural areas.

After we left the homestead in Northern Minnesota and made our home in Western Washington, the country was plunged into one of the greatest Depressions that the United States had ever experienced. Bank failures and loss of jobs brought devastation to many. Even youngsters like myself, who had been encouraged to save money, had to learn that the $140 I had deposited with Prudential Savings in Seattle was lost. I had deposited this modest amount in small sums with money earned from picking bags of moss. The moss was sold for 25-cents a bag to a local nursery. Another source of making a dollar was to peal casscara bark. This bark was dried and broken into inch-square pieces. This bark was then sold for medicinal purposes, usually for a few pennies a pound. Another source of money was the picking and sale of wild blackberries. The berries were found in areas that had been previously logged. It was a very popular item at our roadside stand and would bring $1.00 per gallon.

With the Depression, most of the lumber mills and logging camps shut down. Families who lived in town or in company houses were soon in desperate straits. They could not pay their rent and were seeking housing as well as food and clothing. Lack of food and clothing was critical and many stories circulated telling about the efforts to help those in need. Living on our "Stump Ranch" had its hardships, but also its advantages. During the Depression years we always had plenty of food. There were milk, cream, eggs, chickens and pork, and all the vegetables we could eat. Anything that had to be stored was canned in fruit jars.

Clothing and shoes for school was a major problem. We were usually able to make a few dollars each summer. One source was to pick strawberries at a commercial grower in Hobart, Washington. My sisters and I would leave home at 5 A.M. and drive the 20 miles to the farm in Hobart. We would be home at 3 P.M. after picking strawberries from 6 A.M. to 2 P.M. For our efforts we received one-cent per pound. In one three week season I picked 2,300 pounds of strawberries. Part of this effort was to do better than a lady who had picked 1,900 pounds the year previously. She accused me of never eating, never stopping, and being constantly on the run. Nevertheless, I beat her by well over 400 pounds of berries that summer. The $23 that I earned paid for school clothing and other school items.

The Depression bred those who would steal items that they could not pay for. On one occasion, when our family was at a school program, we had 200 hens which were just old enough to begin laying eggs stolen. On another occasion, one of my sisters and I were home alone. We heard a commotion in the chicken house which indicated to me that the chicken thieves had returned. Grabbing Dad's 12-gauge single barrel shotgun and a couple of shells, I told my sister to lock the door when I went out. I crept past the woodshed and stopped behind a large woodpile. Pointing the shotgun in the direction of the chicken house and the chicken noises, I announced as loudly and as quickly as possible "Stop where you are or I will shoot--Bang". I pulled the trigger and at the same time I said "Shoot" with my thumb of my right hand against my nose. I ended up on my back believing I had torn my nose off. I picked myself and the gun up and ran back to the house. As I got to the door, I heard a car make a hurried squealing departure. When my parents came home I told them what had happened and my dad said he would go out and see if there were any "dead bodies". He said I probably did not hit anyone but I might have scared someone to death. At any rate, my efforts were embedded in the chicken house wall for as long as the chicken house stood.

The fact that the farm was bordered on one side by the Sunset Highway and the other side by the Northern Pacific railroad meant that the Depression brought many hungry travelers to our door. My mother seldom denied a request for a "hand out". Some of the travelers asked if we had work that they could do for food. Others asked for permission to sleep in the barn which was always denied. She would give them soup or a sandwich but she did not want strangers sleeping in the barn which was understandable because some of them did smoke.

By the time the Depression was in full swing, my dad had paid for the "Stump Ranch" and was out of debt. This was fortunate since many people had to move from their homes due to nonpayment and foreclosure. Even being out of debt, it was still difficult to save enough to pay the taxes, buy the gasoline necessary to haul the eggs to market, and bring home the needed chicken feed. Eggs did not bring a very big price but it was enough to pay for the feed and to have few dollars left over.

During the early 1930's and during the worst of the Depression, my dad could not find a job so again he ventured into "Gyppo" logging. This involved buying or contracting for the timber and then getting it to whatever market was available. He logged for fir, maple and alder. The maple and alder was sold to an alder mill in Issaquah and eventually ended up in furniture.

One experience we had during the Depression happened on Christmas Eve. We wanted to attend services at the Bethany Lutheran church in the north part of Seattle. We had enough gasoline for the trip, but the tires were questionable. We drove the Sunset Highway by way of Renton. We had our first flat tire before we got to Renton. A spare tire was put on and we got as far as the Rainier Valley in Seattle when the second tire blew. We limped into a service station that fortunately was still open. It was manned by two young men who, I am sure, had started to celebrate via the bottle, long before we arrived. My dad asked them if they had a used tire that would fit our 1929 Chevrolet. They said "Sure, we'll find something for you". One of the young men jacked up the car and proceeded to pull the flat tire. In the meantime, the other attendant had found a tire that was better than any we had on the car. In a few minutes the good tire replaced the blown-out one and we were back on all four wheels. My dad, who told us later that he had only $2 in his billfold, asked how much he owed them? They said "Nothing, just have a very Merry Christmas". We got to the church in time for the program and I am sure Christmas had a little deeper meaning for all of us that night.

The Depression years brought many people to the Pacific Northwest. Some of our relatives came from Minnesota. They were destitute and needed help in the form of food and a place to sleep, and to eventually try to find work. There were times when it was difficult to walk through the house without stepping on sleeping bodies. Yet, no one complained. There was usually plenty of food, though variety might be lacking. The crusty homemade bread that mother baked daily would keep us from dawdling on our way home from school. The first one home got the best part of the bread--that was the heel or crust. Spread the crust with fresh butter and blackberry jam and you had the very best. mother would add to the bread fare by making Norwegian flat bread called "lefsa." It was made with potatoes and other ingredients. When you spread butter and jam on lefsa you then rolled it into a tight roll. This Norwegian sandwich led one of my school friends to steal my lunch. I learned 30 years later who the culprit was, when he confessed he had taken my lunch because he loved the lefsa bread that my mother put into my lunch box. I forgave him, but told him he could have at least left his own lunch for me instead of throwing it away.

With the chickens, cows and the garden, we had sufficient food. The difficulty was finding money for shoes, clothing and shoe repair. Children can be very hard on shoes if they walk and run over a mile each way to school. Add the rough paved highway and wet rainy weather to the picture and you can see why my dad did shoe repair in the evening. He would buy the heavy leather which he would cut out for the half sole and fashion, trim and attach to the shoes. He also repaired worn heels and patches on the upper part where necessary. I was always proud of my new "soles" and the envy of my friends whose dads could not repair their shoes.

I started high school in the fall of 1931 and, as I said earlier, we scrounged for every dime in order to buy school clothing and school supplies. We knew students who did not go to high school because they could not buy the clothing they felt they needed. My high school teachers were my heroes. They opened so many doors to new learning and new ideas in spite of low wages and checks that they could not cash without taking a discount of 20%. Many of the teachers encouraged us to believe in ourselves and not give up on the idea of attending a university or college in spite of the Depression economy. In spite of this encouragement, only 12 of the 65 graduating students in my class went on to higher education. We really needed a G.I. bill for Depression students like the G.I. Bill for World War II veterans.

There was no school bus service for students who participated in school sports or school dramatic plays. It was necessary to either hitchhike or walk. There were many many times when the four miles to our home was negotiated on foot. This was not bad except when it rained, and it did rain in the Cascade foothills where we lived.

In the spring of 1934, heavy rains and a combination of wet snow caused a multiple tragedy within a mile of our home. All the conditions were right for floods: The steep hill sides just south of High Point were drained by one of the main tributaries of the East Fork of the Issaquah Creek. The soil on the hillsides was saturated and the slides carrying rocks, stumps and logs slid into the creek bottom and began to form a dam. This continued until the dam was 60 to 100 feet high when it burst carrying a wall of water and debris toward the sleeping town of High Point. Standing directly in the flood path was the two-story home occupied by Gus Johnson and his family. Gus was a friend of my father, and they had worked together in the logging camps.

There was no warning or flood alert, just the roar of the raw power of nature at its worst. The Johnson home was cut in half with the upper half holding the mother and three of the children. It stopped when it hit the raised highway. The mother and the children suffered only bruises and shock. The father and Gus Jr. did not fare well. Gus was found in the mud and debris that filled lower half of his house, holding little Gus over his head in an effort to save him from the water. Both father and son were dead.

A duplicate of this tragic flood occurred two miles east of High Point where another tributary of the Issaquah Creek flooded two hours later in the morning. A home was swept away with logs and stumps out onto the farm. Fortunately, no one occupied the demolished home so the tragedy that occurred in High Point was not repeated. It was, however, several days before the road was cleared and in use.

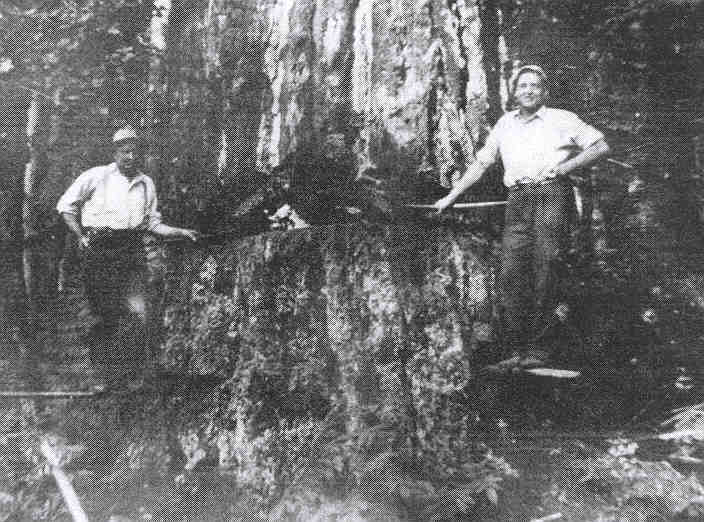

My father purchased a stand of timber that bordered the highway between our home and the town of Preston. He wanted to begin logging in the spring of 1934 and, in order to help him, I did some special assignments so that I could leave school two weeks early in my Junior year. In addition to second growth fir, the timber plot included a number of large old growth trees that had been left in the early logging. These were carefully taken down to get the maximum amount of old growth logs as possible. Most of the old growth logs were purchased by a Seattle plywood mill. We had to get the timber out to the landing by the highway by the use of a crawler diesel tractor. The second growth timber was sold to the Preston Mill Company.

Located in the same area as the old growth fir were several cedar logs that were partially buried under moss, dirt and good sized tree roots. Some of the downed cedar trees were six to eight feet in diameter. The cedar was solid even though some of it had been down for a hundred years based on the age of the larger trees that grew on the cedar log. The cedar was cut in four foot lengths and then split into manageable pieces.

When the blocks of cedar arrived at the shingle mill, they were then cut into two-foot lengths so that they would be ready for the saws and the shingle sawyers.

We finished the logging on that stand of timber in late August. The experience had been very good for me, in addition to making enough money so that I could put some of it into a "College Fund."

My dad and I falling an old growth fir. We are standing on "spring boards".

The High Point Mill Company got most of its timber from the hills to the south of town. A tramway was designed to let the logs down the steepest last mile. The logs were brought to the tramway landing by a railroad system that circled the mountainous slopes. The tramway was large and consisted of a series of large concave wheels that rolled on rails made of logs. A steam donkey engine located at the mill pond served the main mill and would pull the empty tramway up the hill to the railroad landing. When the tramway was loaded with logs another steam donkey engine would let the loaded tramway down the hill and to the mill pond. It was a popular forbidden sport to ride the empty tramway up the hill and then jump off before we were caught. We called the railroad the "Wooden Pacific". My friend, Vince Nelson, was the envy of all of us because his dad was the logging superintendent and as a consequence Vince rode the "Wooden Pacific" whenever he wanted to. Vince stayed in the logging industry and retired as a successful logging contractor in the vicinity of Monroe, Washington.

Another source of entertainment was a two-mile water flume that flowed from Upper Preston to Lower Preston. The main mill was located in Upper Preston where the lumber was rough cut from logs and then floated to Lower Preston in the flume. At Lower Preston, the rough lumber was planed, finished and dried. The finished lumber was shipped out of town by railroad. The young adventuresome boys would use the rough lumber to make a raft and then climb aboard and float all the way to Lower Preston. This activity was strictly forbidden and dangerous since some of the lumber pieces were large and the current in the flume was very swift in places. Fortunately, through the vigilance of the "flume walker" and good luck, no one was injured.